Hi, My Name’s “No, No! Bad Dog!”

We’ve all seen this joke, but behavior

problems are no laughing matter. They are, in fact, potentially life

threatening to your pet. Behavior

problems continue to be the leading cause of relinquishment and euthanasia of

pets in the United States.1-3 Most of the pets given up to shelters

because of behavior problems will end up euthanized. There are so many

‘well-behaved’ orphaned pets out there needing homes, that the ‘bad’ ones don’t

usually get a second chance. Adopting a pet with a behavior problem takes

patience, commitment, a lot of time, and sometimes a lot of money - an effort

most people aren’t willing or able to make.

The sad thing is that most of the behavior

problems that pets are relinquished for could have been avoided all together with

the appropriate training. Unfortunately, many owners don’t know that training

in puppies and kittens needs to start as soon as they get them, or earlier. And

that they (the people!) need the training more than the pets do! Given consistent

signals, your pet can and will learn quickly and eagerly how to be a

well-mannered member of the family. However, we tend to let them get away with

‘cute’ behavior when they are small and young and then wonder why they jump all

over us when they weigh 80 pounds.

Here are a few of the common ‘myths’ about pets that can lead to BIG trouble for you and your pet. These misconceptions may increase the likelihood that a pet will develop a behavior problem and, thus, can lead to the pet's abandonment or euthanasia.

MYTH #1

"Puppies shouldn't go to puppy classes until they have had all their vaccinations, or they will get sick."

|

Figure 1 happy pitbull

|

Despite the growing body of data supporting the benefits of proper socialization, many people continue to be skeptical about the safety of puppy classes and the critical importance of these classes to their pets' long-term health. Classes held in an indoor (and, therefore, easy-to-sanitize) area and restricted to puppies of a similar age and vaccination status are unlikely to lead to disease outbreaks. (To read a position statement on puppy socialization recently released by the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior [AVSAB], go to http://www.avsabonline.org/.)

Dogs are best able to form new relationships with those of their own and other species and to adapt to new stimuli in their environment (habituation) between the ages of 4 and 14 weeks. During this period, puppies begin demonstrating startle reactions to sound and sudden movements as well as fearful body postures. Unsocialized puppies do not learn to discriminate between things that are truly dangerous and those that are not. Such puppies are likely to become increasingly fearful of novel objects, people, and environments.7 Proper socialization during this period is critical if an owner desires a dog that is tolerant of other people and animals and that is unafraid of new environments and situations.

Pet owners need to learn what constitutes appropriate socialization. Simply taking a puppy to a dog park and turning it loose with a group of dogs does not necessarily socialize it. Proper socialization means exposing the animal to a novel stimulus in a way that does not cause fear and should be an enjoyable, positive experience. Many dog owners force their dogs into interactions when the dogs are already showing signs of fear. This forced interaction only serves to convince the dogs that the particular situation or person is terrifying and to be avoided at all costs in the future.

Well-run puppy classes are the easiest way

to expose a dog to novel people, dogs, and situations. In a good puppy class,

puppies will be exposed to children, men in uniforms and hats, wheelchairs,

umbrellas, and other stimuli that are likely to frighten older dogs that have

not had those experiences.10,11 Be aware that some trainers label a

class a puppy class when it is primarily aimed at teaching basic

obedience.

Major imprinting takes place between 4 and

14 weeks in cats as well. Socializing young kittens with lots of handling,

riding in a crate, and meeting new people is especially important.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many places that hold kitten classes. (If you are

interested, check out www.pawfectmanners.com)

Exposure to many different people, noises, handling, and environments is

extremely important at this age in both dogs and cats.

The fact is, more pets are likely to die because of behavior problems than of infectious diseases such as parvovirus infection or distemper, so proper socialization is critical. Ask us about our puppy/kitten training consultation.

MYTH #2

"My dog is aggressive/fearful/shy because she was abused as a puppy."

|

Figure 2 scared chihuahua

|

Certainly, if a dog is acquired after 6 months of age and is fearful, no one can be certain that it was not abused. But by focusing on that possibility, we fail to emphasize the more common causes, and we miss an opportunity to learn what to do to help prevent and treat fear-related behavior problems. Behavior problems, especially those based on fear or anxiety, when ignored will almost always worsen with time. It’s sad, because with just a little training, often these fears and anxieties can be decreased dramatically, thus making the pet much happier and safer to be around.

Although we still have much to learn about

the genetics of behavior, it is well-documented that fearful or shy behaviors

are highly heritable traits.14,15 However, the expression of these

traits will also be influenced by learning and the environment. Dogs can be

habituated to the stimuli that cause them fear by using properly designed

programs of desensitization and counterconditioning. These programs can be

highly effective, especially if started as soon as the problem is identified.

The longer the problem exists, the harder it is to treat. Do not ignore a

problem until it worsens to such an extent that your bond with your pet is

damaged and treatment becomes more costly, difficult, and time-consuming.

The

fact is, few dogs that exhibit these ‘don’t hurt me’ behaviors have been

truly ‘physically’ abused. But if you get yelled at often enough for doing something,

you’d cringe too. Often the dog has not been taught the appropriate behavior,

like eliminating outside, and so is ‘punished’ more frequently for accidents

than it is rewarded for doing the right thing. This leads to the dog

associating a mess on the floor with your displeasure and they offer

appeasement behaviors, like crouching, rolling over or even submissive

urinating, to show you that they are harmless and keep you from being angry at

them. They don’t truly understand you are angry because they pottied in the

house 20 minutes ago, they just know that if the mess is on the floor and you

are around, they’ll get scolded. (see Myth #5)

MYTH #3

"This new medication will treat your pet's [insert behavior problem here]."

|

Figure 3 pill

|

While the development of pharmacologic agents to treat behavior problems in pets has brought much-needed attention to the frequency and seriousness of pet behavior problems, many people appear to have missed an important part of the educational message. These psychotropic medications are just one tool for treating behavior problems. Medications rarely, if ever, cure a behavior problem when used alone. Sometimes, they can suppress behavior enough to temporarily satisfy an owner's desire for change, but the positive results are often transient unless a behavior modification protocol is also included.16

A good example would be a dog with a

thunderstorm phobia. If thunderstorms are relatively uncommon in the area where

the patient lives, the owners may be satisfied by giving a prescription

medication that also sedates the dog. If the owner can be home to medicate the

dog whenever thunderstorms are likely, then the medication may be sufficient to

suppress the signs of the phobia, help the dog feel better, and make the owner

happy. Over time, however, a higher dose may be required, and the dog might

eventually stop responding to the drug. But if a behavior modification program

of desensitization combined with counterconditioning was also instituted, the

dog could learn not to fear thunderstorms and eventually may not need

medication.

The fact is, psychotropic medications

are not cure-alls, but they do help relieve anxiety, may help to calm a dog,

and, most important, can raise the threshold for responding to stimuli, putting

the dog in a state of mind in which it can learn the new tasks that a behavior

modification program is intended to teach it. Ask us for a consultation if you

think your pet is experiencing fear and/or high anxiety during storms or other

events. Together we can develop a plan to help your pet cope.

MYTH #4

"Dogs that are aggressive are acting dominant."

|

Figure 4 barking dobie

|

Aggression is more likely due to fear or anxiety than to dominance. The terms dominance and dominance aggression are probably the most overused and misapplied terms related to animal care today. And worse, a misunderstanding of aggression and dominance has resulted in training methods that make no sense from an ethological point of view and can cause a lot of harm. For almost 20 years, veterinary behaviorists and many nonveterinary animal behaviorists have been trying to spread the message that coercive and punishment-based techniques are not appropriate for treating a dog with any type of aggression.18-20 Those who believed in the necessity of such techniques based their beliefs on wolf behavior. However, for a variety of reasons, it is inappropriate to strictly compare dogs to wolves.21,22

A dominant status is maintained by subordinate animals readily deferring to dominant animals.19 Dominant wolves do not force subordinate wolves onto their backs. Subordinate wolves roll over to clearly demonstrate their deference. Therefore, the idea that by forcing dogs over onto their backs we are demonstrating our dominance and teaching them to be submissive is not only ethologically unsound—neither dogs nor wolves do this—but is also dangerous. Owners routinely get bitten when trying this procedure on an already terrified and aggressive dog, and the only thing the dog learns is that people are indeed terrifying and unpredictable.

Appropriate training for any dog, dominant or not, requires teaching the dog that the owner is the leader19,20,22 and involves being calm, consistent, and trustworthy. Most qualified behaviorists recommend using a version of the no-free-lunch or learn-to-earn protocol. This regimen requires that the owner ask the dog to respond to a command (e.g. "sit") for every resource the dog desires (e.g. food, walks, play, attention). The worst thing that can happen to a dog with this protocol is that it does not get what it desires. Maintaining this protocol teaches the dog to defer to its owner. These command-response-reward interactions also make the owner interact with the dog in a trustworthy and predictable manner, thus relieving the anxiety that many dogs have after undergoing inappropriate training.

Sadly, ‘dominance aggression’ seems to be the diagnosis du jour, and dogs are labeled as dominant because they resist going into their kennels, having their nails trimmed, or being bathed (all while clearly showing signs of fear). We have even seen dogs labeled dominant for demonstrating signs of separation anxiety.

The fact is, aggression is more often

related to fear or anxiety than to dominance. Using physical force or

punishment to get a desired response only leads to more aggression in your pet.

MYTH #5

"See how guilty he looks? He knows what he did was wrong."

|

Figure 5 bulldog

|

This myth probably results in more unintended animal abuse than any other and often arises because a dog is routinely destructive in the house, housesoils, or gets into trash cans. Most owners will be quick to insist that the dog "acts guilty before I even know what it has done!" This misconception arises for two primary reasons: 1) The owner anthropomorphizes, and 2) the owner cannot read normal dog body language. The lowered head, tucked ears and tail, and avoidance behaviors that most clients label as guilty looking are ‘appeasement’ behaviors. The dog is demonstrating submission in an attempt to turn off the anger that it is either reading in the owner's body language or expecting from the owner because of previous experience with similar situations.

One way for the owners to understand this

concept and see it in action is for them to perform the following experiment:

Leave, sneak back into the house, turn a trash can upside down, spread trash

around, sneak back out, and then return home later as you normally would. If

the dog has had time to discover the mess, it is virtually guaranteed that the dog

will demonstrate the same behaviors it would have demonstrated if it had made

the mess itself. The dog has made the association between the presence of a

mess (whether it is feces, urine, or trash) and an angry owner. It has not made

the association between its behavior and the angry owner.

Punishing

bad behavior is not the best option.

For

punishment to be effective, it must involve three principles:

1)

it must be applied within one or two seconds of the inappropriate behavior

2)

it must be applied every single time the behavior is performed

3)

it must be potent enough that the dog will seek to avoid it in the future but

not be so aversive as to frighten the dog.25

The AVSAB has issued a position statement on the use of punishment for behavior modification in animals as well as guidelines on using punishment ( http://www.avsabonline.org/ ). Dogs that experience fear or anxiety during training will not learn as well and, as already mentioned, are more likely to learn that people are scary and unpredictable. Since even the best trainers are often unable to use punishment according to these three principles, the chances are great that the average pet owner will do more harm than good. In short, it is much easier to teach a dog what you want it to do by rewarding it for appropriate behavior than it is to teach it what not to do by punishing it.

The fact is, pet owners need to understand that animals make associations between events that consistently occur in association with each other. Punishing a dog for something that it did, even a few minutes ago (no matter how the dog is acting), does not teach the dog what you don't want it to do - it teaches the dog that people are to be feared.

MYTH #6

"If you use treats to train a dog, they'll always be needed to get the dog to obey your commands."

|

Figure 6 shih tzu

|

Positive reinforcement, an excellent way to teach an animal a new behavior, requires that you give something pleasant within one or two seconds of the occurrence of the desired behavior.26 And, the animal will learn most quickly if the reward is given every time it performs the desired behavior, which is called continual reinforcement.27

But once the behavior is acquired and a verbal or hand cue is attached, the behavior is best maintained when the reward is given intermittently.27 This principle is the same one that keeps people putting quarters into slot machines. Slot machines only pay off intermittently, but people continue pulling that handle on the chance that the next time they will get the reward. Intermittent reinforcement is powerful, and behaviors trained with it are resistant to extinction, but if we used it to teach new behaviors, progress would be slow.27 With intermittent reinforcement, the dog never knows for sure whether it is going to get the food. The reward is presented and given only after the desired behavior is performed. In contrast, a bribe is shown to the dog when it is asked to perform the behavior. The dog knows it is going to receive it.

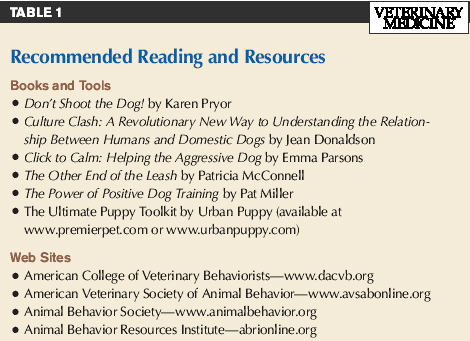

The fact is, when used appropriately, food rewards are an excellent and effective way to teach a dog new behaviors. Once a dog learns a behavior, these rewards should be used intermittently. One of the more common mistakes a pet owner makes is to think that a dog knows a behavior long before it actually does. To learn more and to help interested clients learn more, refer to the books and other resources listed in Table 1.

|

MYTH #7

"Dogs chase their tails because they are bored."

|

Figure 8 dalmation spin Getty Images |

This statement is a dangerous oversimplification of a problem that we still have much to learn about. Repetitive behaviors such as tail chasing and pacing have long been noted and studied in confined domesticated and wild animals. A commonly held belief is that these behaviors are a response to a barren or somehow inappropriate environment.28 However, the evidence suggests that what initiates these behaviors and what maintains them may be two separate mechanisms.

In addition, these behaviors are often a

response to an underlying medical condition. Recent studies have documented

that at least two problems (psychogenic alopecia in cats and acral lick

dermatitis in dogs) previously thought to be primarily behavioral have a good

probability of being primarily medical problems.29,30

People also need to understand the role that learning may play in behavioral conditions. An animal that discovers that its behavior results in attention—whether good or bad (e.g. being yelled at)—from its owner may continue to perform the behavior even after the inciting cause is alleviated. This situation is similar to a cat that quits using its litter box because of urinary tract disease yet continues housesoiling after treatment because of a learned substrate or location aversion.

The fact is, the cause of repetitive behaviors can be a complicated combination of physiological, environmental, and learned factors.

MYTH #8

"Any trainer can handle all behavior problems."

|

Figure 9 trainer

|

Sending a dog with a behavior problem to the wrong person can be as dangerous as not recommending any treatment. Not all trainers and behaviorists are the same. Anyone can call himself a behaviorist or a trainer without having any education in the field. Making the wrong choice can have potentially devastating consequences to your pets' health and well-being.

Referral to a trainer

Trainers are especially helpful for a pet that needs basic training such as learning to sit, stay, or come on command. A good trainer uses primarily reward-based training, doesn't insist that a pet owner do anything ethologically unsound or dangerous (e.g. trying to force a dog over in an alpha roll), and is willing to work with other professionals such as a veterinarian to develop a plan that works for the individual. The AVSAB has an excellent position statement on behavior professionals and how to choose a trainer ( http://www.avsabonline.org/ ).

The fact is, people should do thorough research before choosing to a trainer or behaviorist. Taking an animal to an inappropriate trainer can exacerbate behavior problems and may have serious consequences.

|

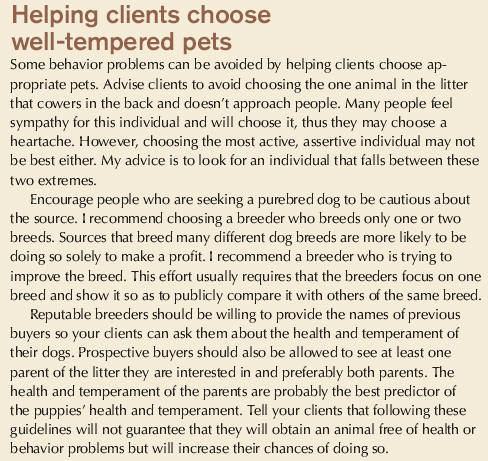

An awareness of the importance of genetic influences on behavior can also be helpful when choosing a pet and a breeder (see boxed text "Helping clients choose well-tempered pets").

The fact is, an animal's behavior is a result of the complex interaction between its genes and its environment. It can rarely be attributed to a single event, and even if it can be, change is still possible.

If you are interested in training classes for your pet, check out www.pawfectmanners.com.

If you feel your pet’s behavior requires medical assistance, please call us at (281) 444-8387 and set up an appointment. The first step is making sure there are no underlying medical problems causing the behavior. Blood work will be run to make sure the pet can take the medication without adverse effects. When you make the appointment, please tell us that it is for a behavior problem so that we can schedule an appropriate amount of time. Schedule at least an hour yourself, so that we can get a thorough history.

This article has been adapted

from:

10 life threatening behavior myths

Valarie V. Tynes, DVM, DACVB

Publish date: Sep 1, 2008

REFERENCES

1. New JC Jr, Salman MD,

Scarlett JM, et al. Moving: characteristics of dogs and cats and those

relinquishing them to 12

2. Scarlett JM, Salman

MD, New JG, et al. The role of veterinary practitioners in reducing dog and cat

relinquishment and euthanasias. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;220(3):306-311.

3. Segurson SA, Serpell JA,

Hart BL. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment questionnaire for use in the

characterization of the behavioral problems of dogs relinquished to animal

shelters. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;227(11):1755-1761.

4. Juarbe-Diaz SV.

Behavioral medicine opportunities in North American colleges of veterinary

medicine: a status report. J Vet Behavior 2008;3(1):4-11.

5. New J, Salman MD, King

M, et al. Characteristics of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners

compared with animals and their owners in

6. Lue TW, Pantenburg DP,

Crawford PM. Impact of the owner-pet and client-veterinarian bond on the care

that pets receive. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232(4):531-540.

7. Scott JP, Marston MV.

Critical periods affecting the development of normal and maladjustive social

behavior in puppies. J Gen Psych 1950;77:25-60.

8. Seksel K, Mazurski EJ,

Taylor A. Puppy socialization programs: short and long term behavioral effects.

Appl Anim Behav Sci 1999;62:335-349.

9. Duxbury MM, Jackson

JA, Line SW, et al. Evaluation of association between retention in the home and

attendance at puppy socialization classes. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2003;223(1):61-66.

10. Landsberg G,

Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Prevention: the best medicine. In: Handbook of

behavior problems of the dog and cat. 2nd ed.

11. Jackson J, Line SW,

12. Dodman NH, Moon R,

Zelin M. Influence of owner personality type on expression and treatment

outcome of dominance aggression in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc

1996;209(6):1107-1109.

13. Voith VL, Wright JC,

Danneman PJ. Is there a relationship between canine behavior problems and

spoiling activities, anthropomorphism, and obedience training? Appl Anim

Behav Sci 1992;34:263-272.

14. Mackenzie SA, Oltenacu

EAB, Houpt KA. Canine behavioral genetics—a review. Appl Anim Behav Sci

1986;15:365-393.

15. Goddard ME, Beilharz

RG. A multivariate analysis of the genetics of fearfulness in potential guide

dogs. Behav Genet 1985;15(1):69-89.

16. Hart BL, Cliff KD,

Tynes VV, et al. Control of urine marking by use of long-term treatment with

fluoxetine or clomipramine in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2005;226(3):378-382.

17. King JN, Simpson BS,

Overall KL, et al. Treatment of separation anxiety in dogs with clomipramine:

results from a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled,

parallel-group, multicenter clinical trial. Appl Anim Behav Sci

2000;67(4):255-275.

19. Overall KL. Canine

aggression. In: Clinical behavioral medicine for small animals.

20. Landsberg G,

Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Canine aggression. In: Handbook of behavior

problems of the dog and cat. 2nd ed.

21. van Kerkhove W. A

fresh look at the wolf-pack theory of companion-animal dog social behavior. J

Appl Anim Welf Sci 2004;7(4):279-285.

22. Yin S. Dominance

versus leadership in dog training. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet

2007;29(7):414-417;432.

23. Bernstein IS.

Dominance: the baby and the bath water. Behav Brain Sci 1981;4:419-457.

24. Drews C. The concept

and definition of dominance behavior. Behaviour 1993;125:284-313.

26. Schwartz B, Wasserman

EA, Robbins SJ. Operant conditioning: basic phenomena. In: Psychology of

learning and behavior. 5th ed.

27. Schwartz B, Wasserman

EA, Robbins SJ. The maintenance of behavior: intermittent reinforcement, choice

and economics. In: Psychology of learning and behavior. 5th ed.

28. Mason GJ.

Stereotypies: a critical review. Anim Behav 1991;41(6):1015-1037.

29. Waisglass SE,

Landsberg GM, Yager JA, et al. Underlying medical conditions in cats with

presumptive psychogenic alopecia. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2006;228(11):1705-1709.

30. Denerolle P,

31. Landsberg G,

Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Handbook of behavior problems of the dog and cat.

2nd ed.

32. Case DB. Survey of

expectations among clients of three small animal clinics. J Am Vet Med Assoc

1988;192(4):498-502.

33. Ader R, Cohen N,

Felten D. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between the nervous system and

the immune system. Lancet 1995;345(8942):99-103.